Financial Crime

US debanking laws, politics complicate financial crime compliance

• 0 minute read

February 19, 2025

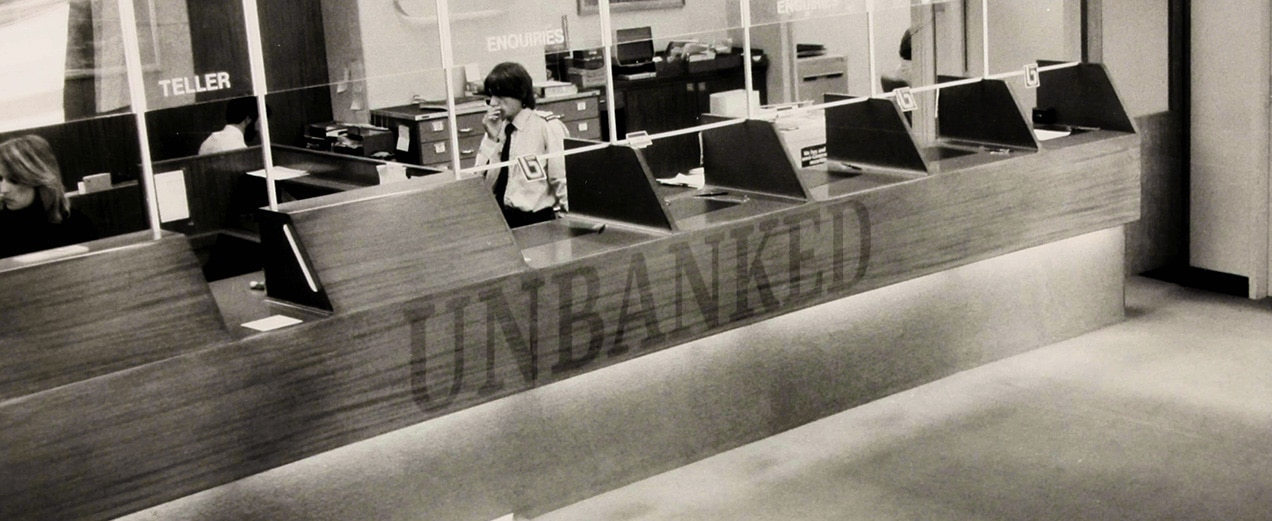

New state “anti-debanking” laws, as well as congressional investigations into the alleged “weaponisation” of agencies that police banks’ anti-money laundering (AML) controls, have complicated financial crime compliance efforts in the US.

Both Florida and Tennessee have introduced “fair access” laws in response to concerns that customers were denied bank services based on their political opinions, religious beliefs or other non-qualitative, biased standards. Conservative lawmakers have been concerned that businesses selling guns, or religious books and merchandise were being victimised by banks seeking to align their customers bases with a so-called “woke agenda”.

Some congressional Democrats and Republicans, however, believe these state laws could jeopardise suspicious activity reports’ (SAR) confidentiality and tip off criminals to law enforcement investigations.

Ungoverning

Federal lawmakers and allies of President Donald Trump have conflated transaction monitoring with “illegal surveillance” aimed at persecuting right-wing and religious groups. New US attorney general Pam Bondi has disbanded the Department of Justice’s Task Force KleptoCapture and refocused the criminal division’s Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) unit and money laundering and asset recovery section to tackle cartels and transnational crime organisations (TCO). The Trump administration then followed up Bondi’s actions with an executive order halting enforcement action on FCPA cases.

These attacks on anti-corruption and AML laws have been ongoing since the last Trump administration, and are part of a philosophy of the deliberate “ungoverning” of the US, according to Jodi Vitorri, professor of practice and co-chair of the global politics and security programme at Georgetown University in Washington, DC.

“The people who wrote the regulatory and Treasury sections of Project 2025 are individuals for whom — through an overlapping series of ideologies, I would argue — aim to take apart the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and [are involved] in the larger ungoverning of [anti-corruption] functions of the US,” Vitorri said.

Confusing

The clash between Trump administration policy and right-leaning ideologies, and current AML rules is confusing and at times contradictory. Compliance officers should be diligent in documenting decisions and timelines related to sensitive cases, where following the rules might draw political heat in the near term but failure to comply might bring enforcement under a different administration.

“If everything starts to fall, then I guess it’s the Wild, Wild West,” said Steve Marshall, director of advisory services at AML solutions provider, FinScan in Pennsylvania. “It doesn’t present any easy answers for folks in financial crime compliance, because the notion of anti-bribery and corruption and AML are part and parcel of the same thing when it comes down to the means by which you prevent and detect that activity.

“As compliance professionals, you need to look at the [anti-financial crime] laws that are on the books, that still have enforcement teeth to them, and take it a day at a time,” he added.

State versus federal

At least another 10 states — namely, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nebraska, South Dakota and West Virginia — have introduced fair access legislation similar to that of Florida and Tennessee. Regulators, lawmakers and financial crime experts worry the state laws, particularly in Florida, may clash with federal regulations. Florida, for example, expanded its law last year to apply to federal- and state-licensed banks that are not licensed but operate in the state.

“The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency has a concern with respect to federal pre-emption on these state laws, and a bipartisan group has written to FinCEN about how these [state laws] may conflict with the AML laws. That bipartisan concern is probably mitigated by the trifecta of Republican holdings in the House, Senate and the White House, which means there probably won’t be any movement to deal with the pre-emption question and in fact, you’ll probably see more movement towards the same kind of laws at the federal level,” Marshall said.

The people most concerned with these conflicts were regulatory and FinCEN officials, whose careers were currently in a precarious position, he added.

Spying allegations

Federal lawmakers have targeted FinCEN with similar accusations of anti-rightwing bias. For example, representative Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), a Trump ally, claimed in a committee report that FinCEN “commandeered financial institutions to spy on Americans” in the wake of the January 6, 2021, attacks on the Capitol building.

However, FinCEN would require a subpoena both to access banks’ information about individual customers, and to demand that banks surveil certain customers.

Jordan’s Subcommittee on the Weaponisation of the Federal Government also took issue with FinCEN’s alerts suggesting banks monitor for terms linked to far-right groups. However, Marshall pointed out that if there was a risk far-right terrorist groups were masking money that was being used for illicit purposes, it was “well within FinCEN’s purview to put out alerts” to banks.